Why is childhood important for our mental health?

Most of us have encountered individuals—perhaps even ourselves—who attribute their current physical, emotional, or mental state to their upbringing. These people often point to their childhood experiences and their parents’ influence as the root cause of their present difficulties.

But is this a valid explanation or merely an excuse? How crucial are our family experiences, particularly our relationships with family members? Moreover, what is the extent of parental responsibility for their children’s mental and physical health, development, and well-being—both during childhood and into adulthood?

In this article, and in future pieces exploring past experiences, childhood, and family relationships, we’ll examine these questions through the lens of attachment theory. This theory seeks to understand how our early experiences in infancy continue to shape us throughout our lives.

John Bowlby (1907-1990), a psychoanalyst, developed attachment theory. He posited that mental health and behavioral issues could be traced to early childhood experiences. Attachment, as defined by Crittenden (1995), refers to “patterns of mental processing of information based on cognitive function and emotional influence to create models of reality.” These patterns typically form in infancy and remain relatively stable throughout life. A child’s primary attachment pattern usually develops in relation to the mother and often extends to subsequent relationships.

1. Innate Need for Attachment

Children have an innate need to attach to a primary caregiver—typically a parent—as it’s crucial for their survival.

2. Continuous Care

A child requires constant care from this primary attachment figure for approximately the first two years of life.

These early years of attachment are encoded as procedural memory, manifesting in two main behavioral patterns:

- Proximity-seeking behavior: Social engagement and participation

- Smiling

- Making eye contact

- Approaching others for social interaction

- Attempting to communicate

- Defensive expressions

- Avoiding or ignoring others

- Physical withdrawal (isolation or avoidance of physical contact, e.g., hugging)

- Tension patterns (aggressive or defensive behavior), expressed through posture and non-verbal communication

Bowlby (1951) argued that maternal care is most critical in the first two and a half to three years of a child’s life.

If attachment is disrupted during this critical two-year period, the child may suffer irreversible long-term consequences of maternal deprivation. This risk persists until the age of five.

3. Consequences of Maternal Deprivation

Long-term maternal deprivation can lead to cognitive, social, and emotional difficulties for the child, including:

- Delinquency

- Reduced intelligence

- Increased aggression

- Depression

- Apathetic psychopathy

4. Child’s Reaction to Separation from the Attachment Figure

John Bowlby and James Robertson (1952) observed that children experience severe distress when separated from their mothers. Even when other caregivers fed these children, it didn’t alleviate their stress.

They identified three progressive stages of distress:

- Protest: The child cries, screams, and angrily protests when the parent leaves, attempting to cling to the parent to prevent their departure.

- Despair: The child’s protests subside, and they appear calmer but remain upset. They reject comfort from others and often seem withdrawn and indifferent.

- Detachment: If separation continues, the child begins to engage with others again. However, they may reject the caregiver upon their return and display strong signs of anger.

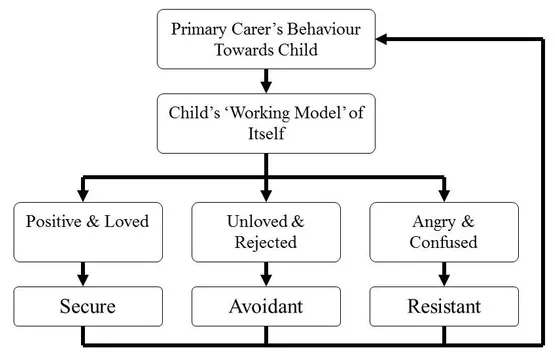

5) Internal Working Models

The child’s attachment relationship with their primary caregiver leads to the development of an Internal Working Model (Bowlby, 1969). This cognitive framework includes mental representations for understanding the world, self, and others.

An individual’s interactions with others are guided by memories and expectations from this model, influencing how they evaluate their contacts with others (Bretherton & Munholland, 1999).

The internal working model has three main components:

- A model of others as reliable

- A model of the self as valuable

- A model of the self as effective when interacting with others

This mental representation guides future social and emotional behavior, influencing how the child—and later, the adult—responds to others in general.

Types of attachment – Focus on secure attachment

Researchers (Ainsworth, Belhar, Waters & Wall, 1978) identified three patterns of attachment in children:

- Secure attachment

- Insecure-avoidant attachment

- Insecure ambivalent

In 1990, Main & Solomon identified a fourth model:

- disorganized attachment.

In this article the focus will be on secure attachment.

Secure Attachment

The mother serves as the primary “regulator” of her child’s emotional state. She helps her child experience joy and contentment, as well as calms and reassures them during various negative emotional transitions.

Children with secure attachments have their physical and emotional needs met by their mothers. They receive care, affection, and love unconditionally whenever needed. Simultaneously, their interaction and communication remain harmonious.

Social Engagement System

The social engagement system develops our capacity for self-regulation, which forms the foundation for a functional sense of self (Beebe & Lachmann, 1994; Schore, 1994; Stern, 1985).

The sense of self is primarily a bodily experience, perceived through sensations and movements. While touch is the main form of communication between infant and parent immediately after birth, visual and auditory stimuli play an increasingly significant role over time.

What Determines Communication Between Children and Mothers?

- Physical contact (touch, hugs, etc.)

- Verbal communication (e.g., through tone of voice)

- Non-verbal communication (mainly through facial expressions)

- Common activities (through play and care)

These elements contribute to the development of the social engagement system, which facilitates social interaction for the infant (and later for the adult) with both the caregiver—their mother—and other people in adulthood (friends, romantic partners, coworkers, etc.). This social engagement system is evident when the baby:

- Makes sounds or shouts

- Cries or grimaces

- Shows signs of anxiety or dissatisfaction

- Smiles

- Gazes

- Seeks interaction with their caregiver

These physical care experiences and the signals the baby sends ultimately determine their initial sense of self and body awareness.

When the child seeks intimacy (care, hugging, meeting needs), a responsive mother gives it generously with love and smiles. This differs from other attachment types, which we’ll explore in future articles.

It’s crucial to note that without adequate development of the social engagement system within a secure attachment relationship, children struggle to create a sense of unity and continuity of themselves across past, present, and future, or in their relationships with others.

This deficiency manifests as:

- Emotional instability

- Social dysfunction

- Poor stress response

- Mental disorganization

- Disorientation

The Mother as the “Secure Base”

According to attachment theory, the mother serves as a secure base for the infant and later the child. This base provides love and “shelter” when the child experiences fear, sorrow, or upset. As children grow, they begin to explore the world, gradually becoming more independent and autonomous. However, they continually seek reassurance that their “secure base”—their mother—remains “always there” for them, regardless of circumstances.

To summarize the key points:

- The quality of interaction and communication between child and mother, even in early infancy

- The child’s assurance that their “secure base” will always be available

These factors significantly influence whether the child, as an adult, will feel secure in interpersonal relationships and develop independence.

- Independence and Resilience to Negative Emotions

When a child experiences unpleasant feelings, they learn through their mother’s responses that they can bear, manage, and move past these emotions. Consequently, as adults, they develop more positive responses to unpleasant or stressful situations. While they acknowledge their dissatisfaction and negative emotions, they possess the “tools” or “mental resources” to manage them effectively.

This transition between negative and positive emotions fosters resilience in the baby and, later, flexible adaptive abilities. As noted by American psychologist and neuropsychology researcher Allan Schore (2003a):

“The process of re-experiencing positive emotion after a negative experience can teach a child that negativity can be overcome and conquered.”

- Sense of Self and Self-regulation

The positive and secure attachment between child and mother cultivates the social engagement system. This system, in turn, develops the child’s ability to self-regulate, forming the foundation for their sense of self and body awareness.

Moreover, as children grow accustomed to receiving love and generally positive responses, they develop a more positive self-image as adults.

- Development of Social Bonds and Sense of Security

Finally, this secure attachment enables two crucial factors for the individual as both a child and an adult:

- The ability to socialize and form bonds with others, promoting authenticity and genuineness in relationships characterized by respect, appreciation, and trust

- The capacity to seek help from close individuals when needed, without:

- Feeling like a burden, unwanted, or vulnerable (“If I ask for help, I’ll appear weak”)

- Attempting to solve practical or emotional issues entirely on their own

Furthermore, this secure foundation allows the individual to avoid the “good child syndrome,” enabling them to assert boundaries and say “no” when necessary as adults.

Conclusion

In conclusion, attachment theory provides a profound understanding of how early childhood experiences shape our mental health and relationships throughout life. The secure attachment pattern, characterized by responsive and consistent caregiving, lays a robust foundation for emotional regulation, social competence, and psychological resilience. As we’ve explored, the mother’s role as a “secure base” is pivotal in fostering a child’s ability to navigate the world with confidence, manage stress effectively, and form healthy relationships. This secure foundation not only influences the individual’s sense of self and ability to self-regulate but also impacts their capacity to form genuine connections and seek support when needed. The far-reaching implications of attachment theory underscore the critical importance of nurturing positive parent-child relationships from infancy. By promoting secure attachments, we can contribute to the development of emotionally balanced, socially adept, and mentally resilient individuals who are better equipped to face life’s challenges and maintain healthy relationships throughout adulthood. As our understanding of attachment theory continues to evolve, it remains a cornerstone in developmental psychology, offering valuable insights for parents, educators, and mental health professionals alike in fostering optimal childhood development and lifelong mental well-being.

References

- Ogden, P., Minton, K., & Pain, C. (2006). Trauma and the Body: A sensorimotor Approach to Psychotherapy. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

- McLeod, S. A. (2017, Febuary 05). Bowlby’s attachment theory. Simply Psychology. www.simplypsychology.org/bowlby.html